Rebecca HOLTOM

Find out who I am and where I work

Artist Painter, Printmaker, Designer

Rebecca Holtom

Works in her studio, Montpeyroux, Hérault

She paints with oils on stretched canvas, wood and primed paper. Monoprints are made with ink spread on glass and pressed with absorbent recycled papers. The drypoint engravings are printed on one of three presses. Painting and printing overlap into areas of design, notably textile block printing. Other techniques put into practice are collage, screen-printing, illustration, ceramics and sculpture. The fundamentals remain in the process of drawing.

Born in 10/09/1964

Nationality French/British

Folkestone Grammar School 1976-82

Canterbury College of Art, Foundation course 1983-84

Norwich School of Art, Fine Art Painting BA 1984-87

After many years of teaching art to children and adults, the turnaround has been made “back to the drawing board”.

Informal ‘workshop swaps’ with other artists remain the order of the day, feeding into the exchange of ideas and method

My Studio in Montpeyroux

Portrait of an Artist – Rebecca Holtom Interview with Rose Doyle

Rebecca Holtom

Rebecca Holtom’s art lives and breathes. It has a fluidity, a lightness of touch that enables hope and makes it a natural fit with the way she lives her life. Holtom draws and paints beautifully her work a passionate reflection of the community and countryside she lives in. An equally gifted printmaker, textile designer and collage maker, she is an artist who brings inspired creativity to the everyday. To family above all. “My children”, she is adamant, “have been my real focus”.

She reminisces, just a little, while putting together a collage in her south of France studio. The space, she says, is both “her lifeline” and the reason they bought the house. An attic room, long and bright, it teams with ideas and designs, with work completed and in progress, with possibility. Cutting and shaping, she recalls how it was her mother, “in particular, who gave me crayons, paper and clay when I was very young”.

Rebecca aged 6, cast cement by Charmain Holtom 1970

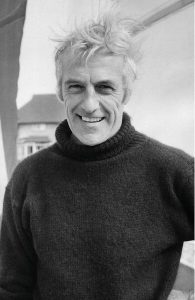

Her mother was sculptor, Charmian Fearnley. Her father was Gerald Holtom, artist and designer of the universal peace sign.

Charmian Fearnley, Royal College of Art, London 1962

Gerald Holtom, Hythe Kent 1975

Peace symbol 1958

Holtom’s very young life was lived “in a rambling house in the middle of Hythe, Kent, with the sea a five minute walk. A lovely place to grow up. We had a big garden with lime, copper beech and horse chestnut trees. My brother Darius and I were taken to museums in London, firing our curiosity in other cultures and traditions. We accepted my Dad’s inventions and my parents’ art as normal.”

Going back to Canterbury Art School after A Levels was, however, a less than normal move from her all-girls grammar school. Graduates were expected “to go to university or into the bank. I couldn’t conform, just couldn’t. The Art Room saved my life. Mr Embry, a teacher who took three of us, Jane, Sam and me, in his clapped out car to the Constable country, we painted all day. I still have some of that work.”

Moving on to Norwich School of Art “had a coincidence. I didn’t know my dad had studied there too”. (He died in her second year). Norwich allowed for a distancing from home, “that was therapeutic, helped me find my path. It was where I began to wake up, get a feel for my life.”

As an Art School, “Norwich was rigorous, very focused on drawing. At a time when other schools were looking at a conceptual way of working we received a classical training. I was interested in landscape painting, loved oil painting, made big triptychs, Francis Bacon gave us a lecture, the head of Fine Art Painting was Anna Maria Pacheceo, Saemus Heaney tutored a poetry writing course and I was guided in painting by Lisa Milroy.” When Botanist and Artist Mary Newcomb arrived as a visiting tutor her “love of ecology and growing things became a huge influence. It was in me anyway, I didn’t need much encouragement.”

Her degree show “went well”. Afterwards, she went back to Kent. When her daughter Alice was born a year later life became a spin of teaching and pub jobs, running a B&B for “sexy French cyclists”, paying off student debts, funding a crèche for Alice. It all ended in a garage sale and tickets for the south of France. “My parents had been there, it was familiar and here I am…” she exhales “…thirty-three years, two more children (Chloe and Gabriel) and a French husband later. I’ve got a French life and I’m a French citizen.”

A lot of art has been made during these years and a lot learned. There’s been experimentation and a great many exhibitions hung. France has been good to her. “I’ve shaken off my roots. I feel it in how I act and speak (apart from my accent !). I don’t know if this is good or bad, but it’s how it is. When I first arrived I did landscapes, pictures of Alice, printmaking, etching. I remember borrowing an old press from glass artist Sally Scott during a really cold winter”.

She met her husband, David, when he arrived at her door to deliver pots of etching ink. . Her fist Montpellier show, “of big black and white drawings and etchings of the local landscapes, insects and the vines, at Club de la Presse” was in Antigone in 1991.

In the years since she has developed “different ways of working, different techniques, ways of using pigment and wax. There’s an excitement in discovering what appears. I’ve always preferred finding out for myself to being told. Drawing and monoprinting are more spontaneous techniques. Drawing happens. Your hand takes over from your brain, it’s simply a fact. It feels very immediate to me. I always think a tube of oil paint is a responsibility, to be preserved for the right thing and not wasted. But oh, I do like oil paints!”

Everything is grist to her working mill, everything everywhere fodder for ideas. Flea markets are especially inspiring. “You find treasure of all sorts; textiles, embroidery, anything. Working in the vines is the same: I see things to paint and work with all time.”

And then, of course, there’s cooking and food. The social part of a meal apart, she “loves inventing and balancing different tastes and colours – though nothing too complicated.” And she likes recycling clothes, making the unwearable wearable. “I’ve always had this thing about waste.”

She tends to “leave work unfinished, ponder, then go back to it. It’s about growth, the organic development of a piece of work. I really admire very disciplined artists but working that way doesn’t work for me.”

If there is joy in Rebecca’s work, and there is, there is also a warning that life, in its bountiful, natural beauty, must be appreciated and given the best care we can give it.

And if Rebecca Holtom has a maxim, it’s that life and art go on developing, in tandem.

Thanks to :

Alice Holtom Rose Doyle Chloé Sanchez Paul McConkey Bernd Unger Oliver Collins